One study 74 found evidence suggesting a feedback cycle of mood and drinking whereby elevated daily levels of NA predicted alcohol use, which in turn predicted spikes in NA. Other studies have similarly found that relationships between daily events and/or mood and drinking can vary based on intraindividual or situational factors 73, suggesting dynamic interplay between these influences. Self-efficacy (SE), the perceived ability to enact a given behavior in a specified context 26, is a principal determinant of health behavior according to social-cognitive theories.

- Interestingly, Miller and Wilbourne’s 21 review of clinical trials, which evaluated the efficacy of 46 different alcohol treatments, ranked « relapse prevention » as 35th out of 46 treatments based on methodological quality and treatment effect sizes.

- Based on activation patterns in several cortical regions they were able to correctly identify 17 of 18 participants who relapsed and 20 of 22 who did not.

- However, recent studies show that withdrawal profiles are complex, multi-faceted and idiosyncratic, and that in the context of fine-grained analyses withdrawal indeed can predict relapse 64,65.

- Rather than being overwhelmed by the wave, the goal is to « surf » its crest, attending to thoughts and sensations as the urge peaks and subsides.

- He adopted the language and framework of harm reduction in his own research, and in 1998 published a seminal book on harm reduction strategies for a range of substances and behaviors (Marlatt, 1998).

Relapse Prevention

Ultimately, individuals who are struggling with behavior change often find that making the initial change is not as difficult as maintaining behavior changes over time. Many therapies (both behavioral and pharmacological) have been developed to help individuals cease or reduce addictive behaviors and it is critical to refine strategies for helping individuals maintain treatment goals. As noted by McLellan 138 and others 124, it is imperative that policy makers support adoption of treatments that incorporate a continuing care approach, such that addictions treatment is considered from a chronic (rather than acute) care perspective. Broad implementation of a continuing care approach will require policy change at numerous levels, including the adoption of long-term patient-based and provider-based strategies and contingencies to optimize and sustain treatment outcomes 139,140. Findings from numerous non-treatment studies are also relevant to the possibility of genetic influences on relapse processes.

- Preventing relapse or minimizing its extent is therefore a prerequisite for any attempt to facilitate successful, long-term changes in addictive behaviors.

- One critical goal will be to integrate empirically supported substance use interventions in the context of continuing care models of treatment delivery, which in many cases requires adapting existing treatments to facilitate sustained delivery 140.

- When euphoric recall and fading effect bias combine, they create a powerful distortion in how we predict outcomes, which is called outcome expectancies.

- But you may have the thought that you need the drug or alcohol to help get you through the tough situation.

- Studies which have interviewed participants and staff of SUD treatment centers have cited ambivalence about abstinence as among the top reasons for premature treatment termination (Ball, Carroll, Canning-Ball, & Rounsaville, 2006; Palmer, Murphy, Piselli, & Ball, 2009; Wagner, Acier, & Dietlin, 2018).

The reformulated cognitive-behavioral model of relapse

Perhaps the most notable gap identified by this review is the dearth of research empirically evaluating the effectiveness of nonabstinence approaches for DUD treatment. Given low treatment engagement and high rates of health-related harms among individuals who use drugs, combined with evidence of nonabstinence goals among a substantial portion of treatment-seekers, testing nonabstinence treatment for drug use is a clear next step for the field. Ultimately, nonabstinence treatments may overlap significantly with abstinence-focused treatment models. Harm reduction psychotherapies, for example, incorporate multiple modalities that have been most extensively studied as abstinence-focused SUD treatments (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy; mindfulness). However, it is also possible that adaptations will be needed for individuals with nonabstinence goals (e.g., additional support with goal setting and monitoring drug use; ongoing care to support maintenance goals), and currently there is a dearth of research in this area.

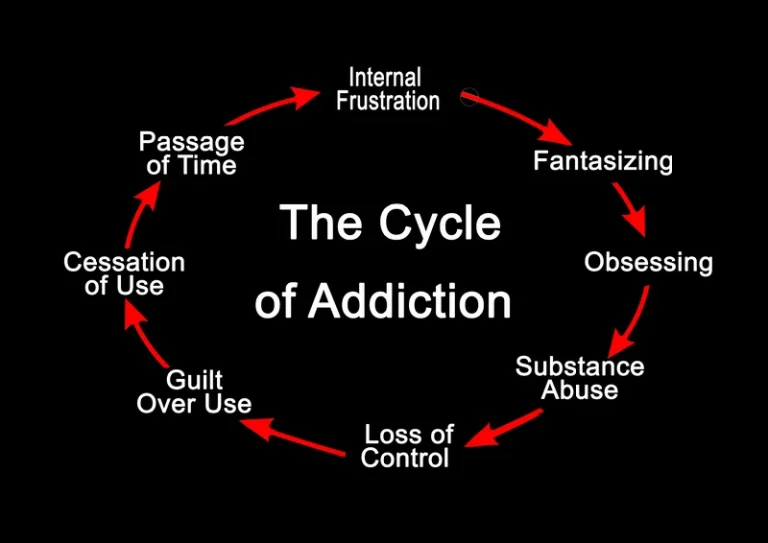

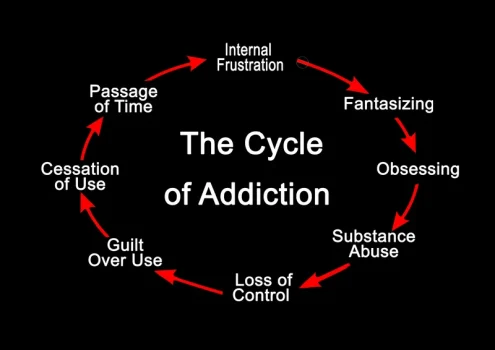

Negative affect

When you are feeling overwhelmed, your brain may unconsciously crave drugs as a way to help you feel better. But you may have the thought that you need the drug or alcohol to help get you through the tough situation. Unconscious cravings may turn into the conscious thought that it is the only way you can cope with your current situation. As a result of stress, high-risk situations, or inborn anxieties, you are experiencing negative emotional responses. Emotional relapses can be incredibly difficult to recognize because they occur so deeply below the surface in your mind.

Temptations neither provoked an AVE nor enhanced self-efficacy in either lapsers or maintainers. Maintainers’ reactions to temptations were nearly identical to lapsers’, except that maintainers felt worse. The data demonstrate the reality of AVE reactions, but do not support hypotheses about their structure or determinants. Administrative discharge due to substance use is not a necessary practice even within abstinence-focused treatment (Futterman, Lorente, & Silverman, 2004), and is likely linked to the assumption that continued use indicates lack of readiness for treatment, and that abstinence is the sole marker of treatment success. Individuals with greater SUD severity tend to be most receptive to therapist input about goal selection (Sobell, Sobell, Bogardis, Leo, & Skinner, 1992). This suggests that treatment experiences and therapist input can influence participant goals over time, and there is value in engaging patients with non-abstinence goals in treatment.

- However, we review these findings in order to illustrate the scope of initial efforts to include genetic predictors in treatment studies that examine relapse as a clinical outcome.

- For example, clients can be encouraged to increase their engagement in rewarding or stress-reducing activities into their daily routine.

- The studies reviewed focus primarily on alcohol and tobacco cessation, however, it should be noted that RP principles have been applied to an increasing range of addictive behaviors 10,11.

- Ecological momentary assessment 44, either via electronic device or interactive voice response methodology, could provide the data necessary to fully test the dynamic model of relapse.

In 1988 legislation was passed prohibiting the use of federal funds to support syringe access, a policy which remained in effect until 2015 even as numerous studies demonstrated the effectiveness of SSPs in reducing disease transmission (Showalter, 2018; Vlahov et al., 2001). Despite these obstacles, SSPs and their advocates grew into a national and international harm reduction movement (Des Jarlais, 2017; Friedman, Southwell, Bueno, & Paone, 2001). Withdrawal tendencies can develop early in the course of addiction 25 and symptom profiles can vary based on stable intra-individual factors 63, suggesting the involvement of tonic processes. Despite serving as a chief diagnostic criterion, withdrawal often does not predict relapse, perhaps partly Sober living house explaining its de-emphasis in contemporary motivational models of addiction 64. However, recent studies show that withdrawal profiles are complex, multi-faceted and idiosyncratic, and that in the context of fine-grained analyses withdrawal indeed can predict relapse 64,65.

Learn From Relapse

Still, some have criticized the model for not emphasizing interpersonal factors as proximal or phasic influences 122,123. Other critiques abstinence violation effect include that nonlinear dynamic systems approaches are not readily applicable to clinical interventions 124, and that the theory and statistical methods underlying these approaches are esoteric for many researchers and clinicians 14. Rather than signaling weaknesses of the model, these issues could simply reflect methodological challenges that researchers must overcome in order to better understand dynamic aspects of behavior 45. Ecological momentary assessment 44, either via electronic device or interactive voice response methodology, could provide the data necessary to fully test the dynamic model of relapse.

Defining The Abstinence Violation Effect (AVE)

Despite the intense controversy, the Sobell’s high-profile research paved the way for additional studies of nonabstinence treatment for AUD in the 1980s and later (Blume, 2012; Sobell & Sobell, 1995). Marlatt, in particular, became well known for developing nonabstinence treatments, such as BASICS for college drinking (Marlatt et al., 1998) and Relapse Prevention (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Like the Sobells, Marlatt showed that reductions in drinking and harm were achievable in nonabstinence treatments (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2002). AA was established in 1935 as a nonprofessional mutual aid group for people who desire abstinence from alcohol, and its 12 Steps became integrated in SUD treatment programs in the 1940s and 1950s with the emergence of the Minnesota Model of treatment (White & Kurtz, 2008). The Minnesota Model involved inpatient SUD treatment incorporating principles of AA, with a mix of professional and peer support staff (many of whom were members of AA), and a requirement that patients attend AA or NA meetings as part of their treatment (Anderson, McGovern, & DuPont, 1999; McElrath, 1997). This model both accelerated the spread of AA and NA and helped establish the abstinence-focused 12-Step program at the core of mainstream addiction treatment.

Shiffman and colleagues 68 found that restorative coping following a smoking lapse decreased the likelihood of a second lapse the same day. One study found that momentary coping reduced urges among smokers, suggesting a possible mechanism 76. Some studies find that the number of coping responses is more predictive of lapses than the specific type of coping used 76,77. However, despite findings that coping can prevent lapses there is scant evidence to show that skills-based interventions in fact lead to improved coping 75. Researchers have long posited that offering goal choice (i.e., non-abstinence and abstinence treatment options) may be key to engaging more individuals in SUD treatment, including those earlier in their addictions (Bujarski et al., 2013; Mann et al., 2017; Marlatt, Blume, & Parks, 2001; Sobell & Sobell, 1995). Advocates of nonabstinence approaches often point to indirect evidence, including research examining reasons people with SUD do and do not enter treatment.